Since I spoke about grip in my National Left Hand Day I feel I should begin with the snare drum grip. Any discussion about grip should begin with the relationship between the stick's stroke and the plane of the drum's surface.

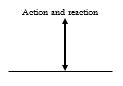

Newton's first law of motion states:

"For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction."

In a perfect world the bead of the stick will strike the drum head at a 90° angle and rebound at that same 90° angle giving it maximum energy.

However the stick scribes an arc in it's movement to and from the drum since the wrist rotates to create the stroke. This means the bead of the stick is forced to rebound from the plane of the drum surface at an oblique angle. Therefore it's important to reduce this angle by keeping the stick parallel to the drum surface as much as possible. By reducing this angle of attack the drummer can recycle this rebound energy for the following strokes.

|

| More rebound energy Less rebound energy |

So what does all of this have to do with grip? Initially drums were slung over the right shoulder causing the left side of the drum to be higher than the right. Playing 'matched grip' would require the drummer to raise his entire left arm so that the stick can address the drum at the proper angle. Switching to the 'traditional grip' allows the drummer to achieve this angle without causing undo stress on the left hand, wrist and arm.

Again referencing the drummer in my previous post, his left arm is raised to a very uncomfortable position and the right stick addresses the plane of the the drum at a height that greatly diminishes the natural rebound making him do all of the work.

So much for the dynamics of the grip, later I'll talk about their advantages and disadvantages.

Comments

Post a Comment